update:February 27, 2025

A special interview for the Toyota Foundation’s 50th year anniversary project

Tsunagari Design Center aims to build a new community that can prevent social isolation of disaster victims

Interviewed by Mitsuru Ohno

Japanese text written by Nobuaki Takeda

Translated by Naoto Okamura

One of the biggest misfortunes caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 was the devastation of local communities. But humans are resilient by nature. Disaster victims have relocated to new places and formed new communities to invigorate their newly adopted communities, despite some relationship challenges at times. What is key in that process is whether residents will be able to find “their own communal place” in such new communities. A case in point is a community building project for post-disaster public housing developed in the Asuto Nagamachi district, Taihaku Ward in Sendai City, Japan’s northeastern Miyagi Prefecture.

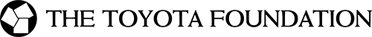

The Toyota Foundation provided grants to this project on three separate occasions -- in 2012, 2014, and 2016 -- which in turn helped revitalize local communities and led to the establishment in October 2016 of a non-profit organization called Tsunagari Design Center (TDC). Professor Nobuyuki Arai of the Faculty of Architecture, Tohoku Institute of Technology, serves as the deputy representative director of TDC. When asked about this interesting project, Professor Arai said, “Since there was no precedent, we were working on this project, with an aim to set a precedent by ourselves.”

Details

- Program

- 2012 Activity Grant Program, Great East Japan Earthquake “Special Subject”, Grant Program for Community Activities

- Project Title

- Building and continuing a new mutually-assisting community in proposing residents-centered reconstruction housing

- Grant Number

- D12-E1-1018

- Grant Period

- August 2012 to July 2013

- Main area of activity

- Miyagi Prefecture

- Abstract of Project Proposal

- With the support of a university and experts, this project intends to conduct activities -- home- and town-building workshops, housing consultation meetings, and door-to-door surveys about residents’ opinions among others --, aiming to create a mutually-assisting, welfare-focused reconstruction of public housing that sustains a community emerged from a temporary housing complex for disaster-displaced people. The project plans to collect opinions from many residents, make proposals on an as-needed basis to the municipal government and businesses, and reflect those proposals in the city’s public reconstruction housing plans as much as possible.

- Program

- 2014年 Great East Japan Earthquake “Special Subject,” Grant Program for Community Activities

- Project Title

- Building a mutually-assisting community embracing public reconstruction housing at three locations in the Asuto Nagamachi district

- Grant Number

- D14-E-0013

- Grant Period

- October 2014 to September 2015

- Main area of activity

- Miyagi Prefecture

- Abstract of Project Proposal

- This project intends to create a new organization that can sustain a disaster-displaced community, sustain a community of displaced residents living in temporary housing, which the organization helps create and connect, form a new mix of community members from different areas smoothly, and build a sustainable and mutually-assisting community organization. Moreover, the project’s Tsunagari Design Center also doubles as an intermediary support organization, which is a contact point for public assistance from the municipality and non-profit welfare organizations and is also tasked to facilitate collaboration and cooperation with nearby neighborhood associations. All these initiatives are collectively termed as “the Astuo Model,” and the project aims to apply this model to other disaster-devastated and displaced districts.

- Program

- 2016 Great East Japan Earthquake “Special Subject,” Grant Program for Community Activities

- Project Title

- A program promoting the use of a shared space for creating communal place in public housing for disaster-displaced people

- Grant Number

- D16-E-0005

- Grant Period

- April 2017 to March 2018

- Main area of activity

- Miyagi Prefecture

- Abstract of Project Proposal

- This project aims to foster a lively community through promoting greater use of a shared space in disaster public housing complex -- a multi-story housing building as well as one-story houses. The former focuses on a public housing complex with many senior residents in Asuto Nagamachi district in the city of Sendai, while the latter aims at a public disaster housing area in Tamauranishi district in the city of Iwanuma.

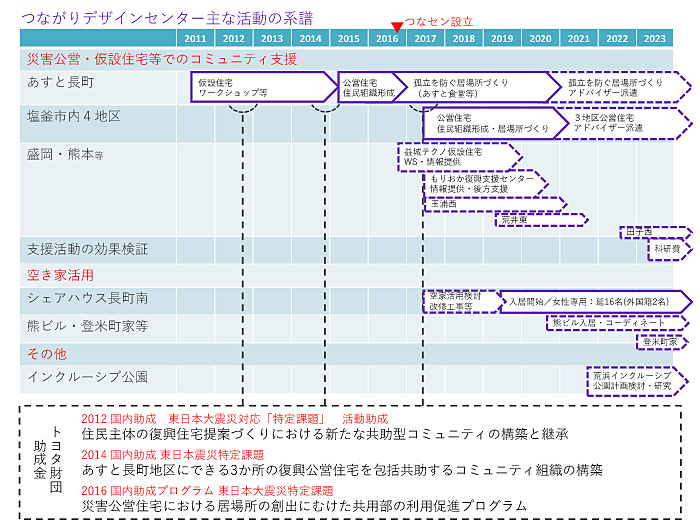

Temporary houses in Asuto Nagamachi, a site for disaster-displaced people from different areas

The project was focused on a temporary housing complex of 233 units, called Astuo Nagamachi Temporary Housing, constructed in Asuto Nagamachi district, Taihaku-ku Ward in the city of Sendai. This was the first prefabricated housing complex built in the city of Sendai after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and displaced residents started moving into these temporary housing units in late April 2011, about a month and a half since the earthquake and tsunami struck Japan’s northeastern region. Most of those residents moved in alone by themselves, except for five groups of 35 households, and a large number of senior residents from various areas began to make a fresh start in their lives.

By residents’ former place of residence, 54.0% used to live in hillside and urban areas of Sendai City, 22.1% came from Sendai City’s coast areas, 11.5% from coastal municipalities north of Sendai such as Ishinomaki City and Minamisanriku Town, 8.0% from coastal municipalities south of Sendai such as Yamamoto Town and Natori City, and 4.4% of them fled from the fallout of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident.

Drawing up public housing plans in collaboration with temporary house residents

The project started with an initiative to sustain and move a newly-built community of temporary house residents to a public housing complex, the next step in the reconstruction process. After this initiative was mostly completed, the project also aimed to foster a new community even after the residents’ move into the public housing, an attempt to take on “the challenge of building isolation-preventing housing units and community” in response to a greying society struggling with growing isolation.

In June 2011, Professor Arai and his laboratory students formed what they called “a support team for customizing temporary house” and began making storage spaces and wooden benches, and started running an outdoor and indoor café. They aimed to 1) improve a living environment through storage making, 2) boost residents’ motivation through their participation, and 3) create a communal space for the residents. “Making storage shelves, in particular, was quite welcomed because many of them had not enough storage space in their temporary houses. To my surprise, people began to gather around when we were making shelves in front of their houses and they started talking to us and among themselves,” said Professor Arai.

As a result of deepening communication among the residents, a steering committee was formed within the temporary housing complex in August 2011 and it was revamped as a neighborhood community association on March 11, 2012, Professor Arai explained. “There was a sense of vibrancy in the temporary housing community back then,” he said.

The community has developed to such an extent that a total of 10 clubs, including for morning exercise, the game of Go, PCs, movies, were formed. Residents told him that they felt safe thanks to the help of community association staffers and volunteers and that they enjoyed activities every day and would like to continue living there.

At the time, Sendai City’s municipal government conducted a survey of disaster victims about their intentions to rebuild their houses. According to Professor Arai, many respondents, including seniors, said they didn’t know how to answer survey questions such as which area they would prefer to live in if they were to move into a public housing complex. “That’s why we decided to provide a place for discussion and launched a workshop for how to sustain and continue a community that was fostered in the temporary housing. That was also around the time when we applied for a Toyota Foundation grant,” he said.

Sendai City’s municipal government has put in place a system in which the government selects proposals from private enterprises and buys facilities built by them or what is called public proposal buyout scheme. Professor Arai believed this would help realize the idea of creating a public housing complex that can retain the community of disaster-displaced residents. This was the reason behind the launch of the workshop, he said.

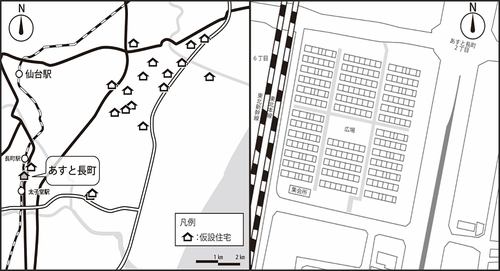

The workshop titled “Let’s think about living in my ideal house and town WS” was held for a total of nine times from March 2012 to January 2013, and as many as 60 people sometimes took part in it. “We continued to talk about what would be the next steps, including what kind of a town they would like to live in after moving out of the temporary housing. In the workshop, we looked at a small-scale model of a public housing complex that would incorporate their wishes, I remember seeing on their faces many participants express hope for the future,” Professor Arai said. “In the end, the residents and construction company officials discussed together and drew up public housing plans and submitted a proposal to the city government.”

Unfortunately, the proposal did not get adopted. But instead, three public housing buildings called Asuto Nagamachi municipality-run housing complex -- a total of 327 units spread across No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 buildings -- were constructed at three locations within a walking distance from the site of the temporary housing. A total of 82 households moved into these new housing units while trying to maintain a communal connection.

Initiatives after the residents’ move into the public housing

The residents started moving into the public housing units in April 2015. Some 25% of the residents came from the temporary housing in Asuto Nagamachi district, while the remaining 75% of them hailed from other government-paid temporary housing units from various areas. To gauge the life of these residents, Professor Arai’s laboratory and TDC jointly conducted a survey of all the households in October 2015, six months after they moved in. The survey found that the residents showed a high level of satisfaction perhaps because of a sense of relief after moving out of the temporary housing. But the survey also found that as high as 45.4% of them said they had no one to talk to other than their family members. Residents told him that they would meet other people less after move into the public housing, while some said they felt it was more fun living in the temporary housing community. “The survey revealed that many households were in a state of near isolation, so we reckoned that offering support was necessary,” said Professor Arai.

At this time, he decided to apply for a Toyota Foundation grant for the second time, for he thought it was necessary to establish a system for mutual support covering all public housing residents at the three locations. As more than 70% of the head of households in the public housing units aged 60 or older, it was considered quite difficult to run a neighborhood association independently on their own. Professor Arai concluded that it would be necessary to provide assistance or set up a system for taking on such a responsibility on behalf of senior residents. For that to happen, a grant money would be indispensable for implementing such an initiative on a pilot basis.

Besides, Professor Arai carried out a survey of groups holding various events at a gathering venue in the Asuto Ngamachi temporary housing. A total of 105 organizations used the venue over a period of nearly four years. Of them, 17 organizations conducted activities more than 10 times. A non-profit organization named Sendai Active Listening Group ranked first by using the venue as many as 71 times. “The newly-built public housing complex also has a gathering venue, so if these groups continued their activities there, I thought, the venue could serve as a place to help prevent social isolation of senior residents. I contacted more than 10 such organizations, and almost all of them said they would like to carry on their activities even at the public housing venue if requested,” he said.

At the same time, the survey findings revealed something very important. Professor Arai took part in the activities organized by these organizations and listened to what resident participants had to say, only to find that the same people participated in each of those activities. And yet, he discovered that a group of participants varied a little from activity to activity. In other words, each of those activities was attended by the same group of participants and thus their connection within that group remained limited, but diverse connections were also being formed through activities done by various organizations. “This may sound quite natural, but I felt that was the key to creating an important communal place for them,” he said. In other words, the fact that diverse organizations conduct their activities, rather than only a certain organization doing so on a frequent basis, proved to be more conducive to creating a less isolating environment. The essence of creating such a communal space is described in detail in a TDC-issued booklet.

Tsunagari Design Center’s foundation and role

In October 2016, non-profit organization Tsunagari Design Center (TDC) was established, with an eye towards building communities that can better deal with an aging and isolated society. TDC launched its activities centered around community building and assistance for running the public housing neighborhood association, as well as research and survey of disaster-displaced people’s new way of living.

To create a communal place for everyone, Asuto Nagamachi district makes the public housing’s gathering venue open to outside people and groups, thereby encouraging their use of the venue for more opportunities for interaction and building a less isolating environment. As such, TDC has been involved even in the stages of studying how to manage and operate the communal space. For instance, water and electricity costs for a gathering venue are normally defrayed by a neighborhood community association’s membership fees. This means that the more frequent the venue is used for various activities, the tighter the association’s budget becomes. This will likely give rise to dissatisfaction among the resident members. Thus, TDC has introduced a system for charging venue users about 500 yen for three hours. What’s more, it has also introduced an online reservation system to make it easier for booking and running the venue, which is likely to lead to greater use of the facility. Furthermore, free Wi-Fi service became available in 2021 to enhance the venue’s usefulness.

In addition, TDC held what it called “Asuto Cafeteria” event during weekend lunch hours one to three times a month, offering about 30 set meals at reasonable prices -- 300 yen for an adult and 100 yen for a child -- and providing a place for eating lunch and enjoying interaction. The cooking was done by other support organizations. A dozen of such organizations, including a local catering service group and a college seminar specialized in training dietitians, took turns to do the cooking and held this lunch event for nearly 100 times prior to the start of the pandemic.

Every time, different menu items, such as hamburger steak, curry and rice, and Chanko hot pot, were offered to allow the participants to enjoy various types of dishes. “TDC’s role was to make arrangements for event dates and who would be in charge of cooking, reception, and accounting, as well as to set up tables and chairs. Since this Asuto Cafeteria is part of our efforts to help prevent isolation, we place counter seats by the window so that a person visiting by him/herself can also feel comfortable. While many of the participants are elderly women, some elderly men have begun to come in by themselves due in part to these efforts,” Professor Arai said.

TDC has also decided to conduct activities for purposes other than social interaction. This is because social activities have often been attended by sociable people who aren’t isolated at all, making it difficult for socially detached people to join. “Every Friday afternoon, we hold smartphone consultation meetings (Tsunaga Rickey), and this helps newcomers to come to the gathering venue and create new connections among them,” he said.

A local welfare service provider Mitsui Co., Ltd. jointly works on Tsunaga Rickey. As part of employment transition support program, young participants of the program engage in helping elderly residents with smartphone use.

Through helping with management and new activities, TDC engages in initiatives to enhance the function of a communal place to drop by. “What we are doing inside the room should be visible from the outside, which helps generate a chance for connection, so the entrance needs to be designed in a way that affords a view of the venue inside. What’s more, in principle, allowing the use of shoes inside and eliminating the need to change to slippers, I think, help lower a psychological barrier and make it easier for people to come in. The place can let in wheelchair users, too,” said Professor Arai, explaining about careful considerations given to physical aspects of designing the gathering venue.

Applying reconstruction community support to other disaster-hit municipalities: Morioka City in Iwate Prefecture, Shiogama and Iwanuma cities in Miyagi Prefecture, as well as Mashiki Town in Kumamoto Prefecture

The know-how accumulated from the experiences of Asuto Nagamachi has been applied to other regions. At the request of Shiogama City’s government, a municipality located on the coastal area north of Sendai City, TDC extended support to the community building effort for housing for disaster-displaced people in the city of Shiogama from fiscal 2018 to fiscal 2020. Assistance was given at four locations, including 170 units at Shimizusawa Higashi Public Housing and 80 units at Nishikicho Higashi Public Housing in Shiogama City, both of which began accepting disaster-displaced people from 2015 through 2017.

Even after one year since the residents moved in, no neighborhood community association was formed and various problems, including altercations between residents, occurred. At the time, an semi-government housing organization, Urban Renaissance Agency (UR), was responsible for operating public housing facilities in the city of Shiogama, and UR asked TDC to begin offering support in April of 2017. “At first, we held meetings to discuss issues with some voluntary residents, but we didn’t see any momentum building to forming a neighborhood community association at all. So, we decided to conduct a survey of all the households by questionnaire to find out about how the residents live and if they are willing to create a community association,” said Professor Arai. “As a result, 39% of the respondents said they would like to join if such an association was formed, while 42.1% answered they would not like to do so. And yet, the residents themselves felt the need for jointly managing their public housing facility. Instead, we suggested that they form a housing management association that would be responsible for collecting a common-area service charge and cleaning up common-use corridors and gardens. As such, they decided to create a management association smoothly.”

Meanwhile, club activities by various organizations, both internal and external, were already held at the gathering place of the public housing facility. To keep up the level of such activities and promote the greater use of the venue, TDC produced and distributed brochures about the gathering place. It also held meetings for exchanging opinions between venue users and the residents’ management association representatives 12 times a year, thereby working to implement initiatives to enhance the communal place’s role in preventing social isolation.

In fiscal 2017, TDC also assisted in the effort to make gardens greener at a collective relocation site in Tamaura-nishi district in the city of Iwanuma, south of Sendai City. In fiscal 2018 and fiscal 2019, TDC encouraged parents and children to use the gathering place and held workshops on pottery and confectionary making, among other events.

Outside of Miyagi Prefecture, TDC took part in a workshop in which prospective residents and experts exchanged opinions about the planned public disaster housing Minami Aoyama Apartment, a facility for inland disaster evacuees in the city of Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. TDC mainly offered advice on how to design a communal gathering place inside the public housing facility. “We made a lot of suggestions about the gathering place, and the use of shoes inside the building has been approved. This not only makes the place more welcoming but also makes effective use of the space by eliminating the space for shoe storage cabinets,” Professor Arai said. “Staff members of Morioka Reconstruction Support Center for Devastated Areas, which is an organization in charge of managing the gathering place, told me that the use of shoes inside proved to be so right!

Furthermore, TDC visited the town of Mashiki in Kumamoto Prefecture, southern Japan, which sustained extensive damage from the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake, and shared its support know-how and expertise gained from the disaster reconstruction process. The use of shoes inside a gathering place for creating a communal place has taken root in disaster evacuee public housing facilities across Japan.

TDC aims to be financially sustainable organization

Then comes the inevitable question: How has TDC secured a revenue source for continuing its activities even after the Toyota Foundation’s grants ended? What TDC has decided to do is to run a share house facility. The idea was generated when a TDC member was asked about how to re-use an empty house owned by an acquaintance. After studying possible uses, TDC decided to use it as a share house so as to generate a revenue. Professor Arai and his students decided what to retain and remove from among remaining furniture and equipment, drew up renovation drawings, and successfully transformed the house into a five-rooms share house facility.

Specifically, TDC has instituted a scheme under which a six-year lease contract is signed between TDC and the landlord and a tenant enters into a sublet lease for a monthly rent of about 30,000 yen. This share house scheme is expected to generate about 800,000 yen in annual revenue. After paying back debts including renovation costs of 3.5 million yen, TDC expects to earn an annual revenue of 1.5 million yen.

“Initially, many of our tenants were foreign students. But we received many inquiries from women and have thus turned the house into a women-only apartment from the second year. In major cities, share house rents are normally much lower than those for one-room apartments, but such price differences are small in rural areas. That made it difficult to attract tenants,” Professor Arai said. “Even so, more people began to realize that living in a share house was more comforting than living alone and tenants started trickling in. From the third year onward, we have been able to secure nearly 80% occupancy rates. As such, the re-use of vacated houses for share house and other purposes is one of the activities for TDC to work on, going forward.”

While it is difficult to secure funding for activities such as disaster-displaced community support, this share house scheme has given TDC a revenue source for covering, if not entirely, the costs of its activities, which in itself is quite significant in terms of business continuity.

Achievements and takeaways from the grants

TDC received grants on three separate occasions from the Toyota Foundation. What kind of achievements has that made?

In fiscal 2012, the first granted project title was “Building and continuing a new mutually-assisting community in proposing residents-centered reconstruction housing.” Since the Sendai City government introduced the so-called public proposal buyout scheme – a system in which the government selects proposals from private enterprises and buys facilities built by them – the grant money was used to conduct activities, including disaster housing proposal-making workshops for disaster evacuees to discuss what kind of a house they would like to live in. “I think workshops gave hope to and empowered disaster victims who had lost their family members and properties. At the initial stages of reconstruction, it was important to conduct an activity for transforming ‘despondency into hope.’” These activities helped deepen trust between disaster victims and supporters. Without trust, TDC could not have continued its activities,” Professor Arai said.

From fiscal 2014, the Toyota Foundation’s second grant was given to TDC for its project “Building a mutually-assisting community embracing public reconstruction housing at three locations in Asuto Nagamachi district.” Support activity for disaster-displaced people often comes to an end when they move out of temporary housing, he said and added that it was very significant that TDC’s support activity has been carried over even after they moved into the public housing units. “The grant money allowed us to help form their neighborhood community association and to hold workshops encouraging support organizations to continue their activities. As a result, we helped develop an independently-run community association and build a mutual network of support organizations for collaboration. These were great achievements,” Professor Arai said. “By identifying how the gathering venue was used and what it would take to create a communal place, we came to learn about what diversity-minded community and communal place should be like. That was a great takeaway for us. I think it was thanks to the grant money that we have become aware of this new value.”

The third grant from the Toyota Foundation was made to the activity that TDC carried out in fiscal 2016, “A program promoting the use of a shared space for creating a communal place in public housing for disaster-displaced people.” Offering greater usability and user value through initiatives, such as introducing the usage fee, building an online reservation system, and installing Wi-Fi connection, has prompted diverse organizations to use the gathering venue, Professor Arai said. “Asuto Cafeteria requires volunteers to do the cooking, but for them to continue, we need to be careful to not overburden them and keep them engaged and satisfied. We have been able to achieve that balance by using the grant money to defray every little cost for having volunteers. In my opinion, paying such careful attention to staffers working on the ground is essential for having a sustainable system in place.”

What Professor Arai has learned through the support activity is that careful examination is necessary for extending support to a community transitioning from an emergency situation to a more normal state. He acknowledges that giving support can serve as an important element of care for disaster victims who suffers great losses, including of people-to-people ties and community solidarity. Over time, however, human relationships can be troublesome at times. “At a time like that, seeking only for a vibrant atmosphere and active interaction can make some people feel uneasy. Under such circumstances, it is important to recognize changes in a given situation and modify the content of activities accordingly,” he said.

What’s more, Professor Arai also feels that the role his university team plays is more significant than expected. “I realized that a university is well-positioned to act as a bridge connecting various stakeholders. When it comes to introducing a new system or new idea, it is not only important for us to explain in detail for better understanding but also necessary for us to win people over. It seems that they listen with an open mind when information comes from university-affiliated supporters,” he said. “For one thing, TDC is characterized by the fact that it has a number of university researchers on its board of directors. With that in mind, we would like to continue with our activity, going forward.”

Those grant-awarded projects have yielded a number of activities, but most notably they have led to the establishment of TDC itself. While it is true that few public housing communities make good use of their gathering venue, TDC has become a leader in creating a communal place for residents by utilizing such a venue. In this process, we have built relationships with various organizations, which in turn has helped us to launch a profit-making business of running a share house,” Professor Arai said. This underscores the fact that many connections made through promoting the grant-awarded projects have solidified TDC’s organizational structure.

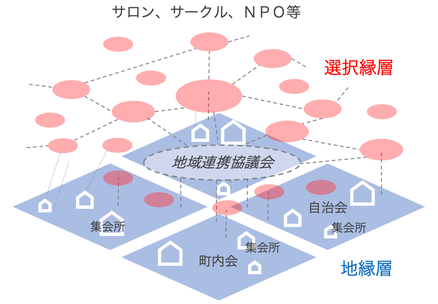

TDC’s future goals and dream

For Professor Arai, the TDC’s immediate goal is to secure a stable source of its own funding further through expanding real estate business for social purposes, such as the management of share house facilities. But “our bigger goal or dream is to establish a system for running a new way of local communities to prevent isolation. For that to happen, we will need to slim down the conventional role of community associations and to build a network of diverse organizations involved at the same time,” he said. “While the conventional way of community management is important, that would not be enough for playing a more comprehensive role. Even for residents, it is unclear to what extent participation is mandatory or voluntary. That is one factor for making it difficult for them to get involved,” Professor Arai said.

Looking ahead, he believes that an organization tasked with management responsibility, just like condominium management associations, will represent a local community and put various support groups and organizations in charge of voluntary activities at a gathering venue, such as tea drinking and other events. In his view, that will help forge various connections and create an isolation-preventing environment. “As we saw in the survey of gathering venue’s use, there is the issue of compatibility in human-to-human relationships. Therefore, it is all the more important to offer various choices to choose from. To encourage diverse groups to use the venue, you need to have a management system in place, including a measure to make it easier to rent such a venue.”

Professor Arai emphasizes the need to consider applying this kind of new community management system to not just a public housing community in the disaster reconstruction phase but also ordinary residential areas in normal times. “Currently, it seems to me that many community associations’ activities have ended up merely pursuing what was considered ideal in the past or what I call ‘all but impossible game to play.’ Instead, it is important to make adjustments to what those community associations and their activities should be really like by taking into consideration the compatibility of community members,” he said.