update:July 18, 2024

A special interview for the Toyota Foundation’s 50th year anniversary project

Creating culture through community art

Interviewed by Naomi Okiyama

Japanese text written by Nobuaki Takeda

Translated by Naoto Okamura

The Laboratory for Global Dialogue, a Tokyo-based specified non-profit corporation, is engaged in connecting people from around the world via online video chat and meeting applications such as Zoom, giving them a rare opportunity in their day-to-day life to meet others from different parts of the world. The organization received grants on two occasions from the Toyota Foundation, first in fiscal 2017 and next in fiscal 2020. In this interview, Mr. Yuichi Watanabe and Ms. Makiko Nakagawa, Secretary General and Director of the Laboratory for Global Dialogue, and Mr. Atsushi Kadowaki, Representative Director of Community Art Laboratory, a Sendai-based general incorporated association, talked about their aims behind the two grant-awarded projects as well as their hopes and prospects for the future.

Details

- Program

- 2017 International Grant Program

- Project Title

- Community art project between afflicted areas of Japan and Aceh

- Grant Number

- D17-N-0256

- Grant Period

- November 2017 to March 2020

- Main area of activity

- Japan (Tohoku), Indonesia (Aceh)

- Abstract of Project Proposal

- The Laboratory for Global Dialogue implemented a project designed to pass on the disaster experiences of people in tsunami-affected areas in Tohoku, Japan and in Aceh, Indonesia, a common challenge facing the two regions. The project helped build a foundation and network for young people’s activities through community art in Aceh, helped apply Indonesia’s disaster tourism knowhow to afflicted areas in Japan, and screened a film, which was produced to pass on disaster experience to the next generation, at the Sanriku International Arts Festival. As such, the project carried out mutual learning activities in both relevant regions of Japan and Indonesia, across various fields covering art, disaster, environment, and tourism.

- Program

- 2020 International Grant Program

- Project Title

- Creating "New culture" through community art projects by Indonesian workers and local people in rural Japan

- Grant Number

- D20-N-0138

- Grant Period

- November 2020 to October 2023

- Main area of activity

- Japan (Kesennuma), Indonesia (Ponorogo)

- Abstract of Project Proposal

- The relationship between Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture in northeastern Japa and Ponorogo, East Java, Indonesia has so far been largely limited to an inflow of Indonesian workers. The Laboratory for Global Dialogue organized a variety of community art events centered around this Japan-Indonesia relationship, and established a model for developing a new form of local culture through exchanges and connections with foreign migrant workers. Among such projects (or programs) were Asia Café, a place for exchanges between residents from abroad and local Japanese residents, and Global Dialogue, an activity for connecting online elementary school children from Kesennuma and Ponorogo.

Indonesia was a common thread in both fiscal 2017 and fiscal 2020 projects, with a particular focus on community art. The concept of community art may not be so familiar to many. What is it all about? “It is about using art to reassess and resolve various issues facing communities by involving community residents, artists, and art activities. What’s more, artists themselves become inspired and apply that inspiration to their creative process, and organizing members like us also change accordingly. It is about providing such an interactive place,” said Mr. Watanabe.

Mr. Atsushi Kadowaki, an artist based in Sendai City, took part in this project alongside Mr. Watanabe and other members. “After the end of World War II, community art was born in Europe on the basis of cultural democracy, an idea that everyone has the rights to access arts and culture and to create artistic things, and community art has since developed in different parts of the world. Speaking of art, people tend to put priority on such criteria as high skills or unparalleled originality. Instead, what I find more appealing is the kind of expression or the way of living that can be generated in ordinary activities and yet can come uniquely from that person,” said Mr. Kadowaki. “As I was searching for words to describe an activity that can help visualize or trigger such things, I came across this existing concept called “community art”. In my view, collaborating on what people are interested in will help deepen understanding of and learning about each other, including different cultural backgrounds, and help boost their motivation. That’s why I have decided to employ a community art-based approach.”

As for the overview of grant-awarded project in fiscal 2017, Mr. Watanabe said, “Tohoku is a region that was hit hard by the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, while Aceh is an area that was devastated from the Sumatra earthquake in 2004. The project was an attempt to transform local communities through developing two-way relationships between these two regions. We primarily worked on community art in Aceh.”

Building local communities through art

According to Mr. Kadowaki, local helpers in Indonesia asked him why he was trying to do art projects in Aceh where there were few art museums or galleries, while it would be more understandable to do so in Jakarta or Bandung. And yet, Mr. Kadowaki told them about his own experiences in Tohoku; he had organized a sweet red bean soup gathering monthly in a makeshift house for displaced residents in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake; those people, called “Hisaisha” or disaster victims, had taught him how to prepare local dishes, in which he saw a wealth of cultural legacy that was not lost even after tsunami waves had washed over their houses; and he and a 88-year-old woman had worked together to create a rap song about her life including her disaster experience. He recounted to the helpers each of those activities constituted what he calls community art. Only then did they understand that what he called art was not something complicated but rather ordinary things that they do in their lives. As a result, many young people came forward with a number of interesting proposals, Mr. Kadowaki said.

From Japan, for instance, a Japanese artist, Mr. Parco Kinoshita, organized an activity in which participants carved wooden dolls in memory of those who had perished in the Great East Japan Earthquake, and he held a similar workshop introducing this method to those Indonesian disaster victims of the Sumatra earthquake. Meanwhile, Ms. Manaka Murakami, also an artist, engaged in an activity that highlighted cultural differences between Japan and Indonesia through the “discovery” of a lone-standing tree in Aceh that withstood the earthquake-caused tsunami, a clear resemblance to the so-called miracle lone pine tree left standing after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Tohoku.

From Indonesia, a young man from Aceh, named Pardi, engaged in staging children’s theater performances to narrate the very sensitive topics of the Sumatra earthquake and a long-running civil war that lasted up until that time in Indonesia. He coordinated an activity conducted by three children support organizations. Another young Indonesian person, Noera, created a whole new dish based on Japanese and Indonesian cuisines and served it at a food booth, seeking to bridge the boundary between two cultures by appealing to the palate. As such, there were as many as 60 activities conducted over a three-year period.

Behind all these projects was a sense of urgency that Kesennuma and Aceh both needed to do something to pass on the tsunami experiences to the next generation. As time goes by, local people’s memories of the disasters become more distant and post-tsunami generations are growing in numbers. “For example, we told them that they would be able to not only conduct interviews and preserve memories in writings but also produce outputs in the form of community art,” said Mr. Watanabe. “A woman who acted as a volunteer leader in the latter part of the project later landed a job at Aceh Tsunami Museum. She has since organized a variety of programs, coordinated a livestream session between Kesennuma and Aceh, and invited us to a tsunami symposium when we made our trip to Aceh the last time. I was very grateful and happy.” Without doubt, community art activities have brought about some kind of change in Aceh people’s behavior.

Moreover, Mr. Watanabe also noted that they were looking to empower young people. “There is this young generation who experienced tsunami in their childhood, received a flood of support from overseas, witnessed an end to the civil war, and saw a transition from war to peace. And then there is another generation who were born after all that and knows only peaceful times. Just like Japan’s post-war baby-boomers did, those young Indonesians who know a little bit about the country’s recent past have become the first ones playing a leading role in Aceh’s reconstruction efforts from the tsunami-caused devastation and civil war. They think of social change and are quite conscious of doing their part in society,” he said. “I feel that this project probably served as an impetus for a generation of young Indonesians with a lot of potential to demonstrate their abilities. I am saying this because after gaining a lot of experiences from our project, some of them have begun to take on leadership roles by planning various activities or launching their own organizations. One of them has become a filmmaker producing a film about the Sumatra earthquake.” Clearly, the project has been able to yield a lot of outcomes thanks in part to the Toyota Foundation’s grant.

2nd project: deepening exchanges at café

Ms. Nakagawa concurred; initially, children in Aceh said they could not do that, she recalled. “But by the end of the project, they told me that they were glad they took part in it. It was very satisfying to hear that,” she said.

The successful outcomes of the first project in fiscal 2017 eventually led to the launch of the second grant project in fiscal 2020.

The second grant from the Toyota Foundation was provided for the Laboratory for Global Dialogue’s another project to be conducted in the city of Ponorogo, East Java Province, Indonesia. “Even before the Great East Japan Earthquake, many Indonesian people came to Kesennuma as fishing vessel crew members. After the disaster, quite a few Indonesian technical trainees came here to work on reconstruction efforts and road repairs,” said Mr. Watanabe. “They came into Kesennuma at a time when the houses and roads were in tatters, aiming to rebuild the city from scratch. So, they have developed a feeling that they were pitching in and playing a role in reconstruction.” He described Indonesian technical trainees as being proud of what they did to help rebuild the devastated city.

However, the situation was different when it came to people-to-people exchanges. “People in Aceh were willing to try as long as it is considered okay religion-wise, so our projects proved to be a great success. Then I came to learn that as many as 300 young Indonesian people lived in Kesennuma in my hometown prefecture of Miyagi. And yet, the local residents I met in Kesennuma told me that they had seen quite a few Indonesian people in town but had not had a chance to talk with them. Local people could have a cross-cultural experience without going abroad. That’s a shame, I thought. I wondered how we should go about creating a space for exchanges. That’s how the second projected got its start,” said Mr. Kadowaki.

“I saw technical trainees from abroad go through various training programs and leave their countries, with hopes and expectations for Japan in their hearts. But at the same time, I wondered if I had been able to do something in return for their hopes and expectations,” said Ms. Makiko Nakagawa, director of the Laboratory for Global Dialogue. “When I thought of what I could do, the first thing that came to my mind was to bring people together. I wanted to let other Japanese people know about the positivity and cheerfulness I feel about Indonesian people. I thought there would be a lot of things to learn from one another,” she said.

In the end, the second project was designed to focus on creating a space for exchanges between residents from abroad and Kesennuma locals, along with working on community art activities. For that purpose, the Laboratory for Global Dialogue decided to rent a café, called Kuru Kuru Kissa Utsumi, in the Youkamachi shopping street near the Kesennuma City Office, on an non-business day once a month to hold what it calls Tsunagaru Asia Café. Participants, both locals and foreign residents in Kesennuma, would cook together cuisines of their home countries and talk about food cultures, with an aim to develop a space for creative exchanges.

“At first, the main theme was to offer Indonesian food and learn about Islamic culture under the name of Indonesia café. But as we have provided this space, local shop owners, children, people from various countries, students and researchers seeking to learn about Kesennuma, and journalists have started to join. Participants exchange information, talk about their personal problems, and cook a traditional new year soup with Kesennuma oysters, and we have also invited members of a local Philippines community to hold their Christmas gathering at our Café. Young locals now play a central role in these activities,” Mr. Kadowaki said. As such, the cultural exchange project has grown wider in scope to include various activities than initially anticipated.

Ms. Nakagawa added, “There was a time when we offered a Philippine porridge, and some Indonesian technical trainees told me that they had something similar in Indonesia. Food served as a gateway to conversation.”

While things may appear to have been smooth sailing, the project in fact came up against a big wall right off the bat. That is the spread of the new coronavirus. Not a few foreign technical trainees were working at food processing companies and could not afford to engage in cultural exchange activities. The project was thrust into a difficult situation. Even after the pandemic began to settle down, the project resumed in a low-key manner initially.

Even so, persistence has paid off. While the number of participants varies depending on the content of programs, the café project has become more widely recognized. “This café has gradually helped foster relationships with foreign technical trainees, which in turn seems to have made them feel accepted by local Kesennuma people. Or local residents’ changing attitudes towards them have made them feel that way. I think both are true, and there has been such a change afoot,” Mr. Watanabe said.

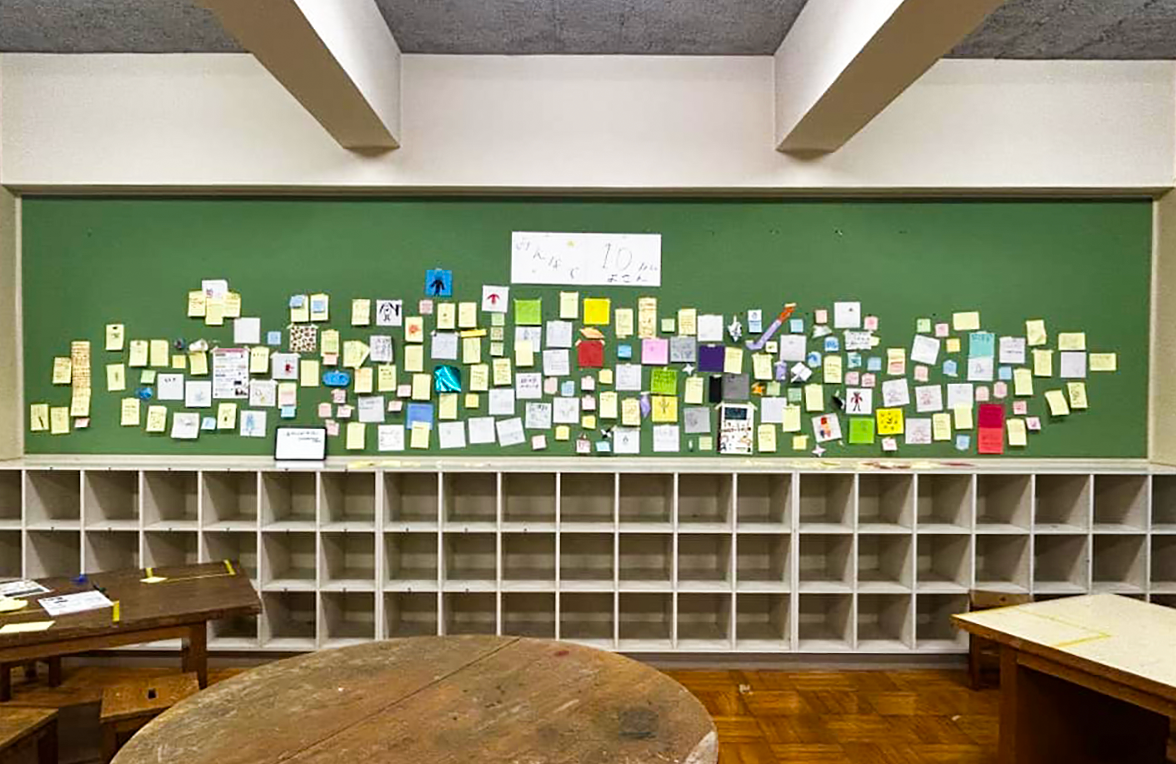

In addition, Indonesian and Japanese children in Tohoku got to know each other via an online platform, an activity called Global Dialogue, has developed into a program titled Kesennuma art elementary school held at Kesennuma Elementary School. These children got to have fun doing a variety of activities – making secret bases, deejaying, drawing pictures, chatting, among other things. This represents what community art is all about. Through this program, some Japanese children have deepened their ties with Indonesia and have begun to show up at Asia Café to interact with young Indonesian people. As such, a new positive trend is emerging in Kesennuma’s local community.

What the future holds for Kesennuma

Mr. Watanabe has grown more confident about positive outcomes of the cultural exchange activities. “For Indonesian technical trainees, I think Kesennuma has become a more comfortable place than other areas,” he said.

If some of these young Indonesians fall in love with Kesennuma and decide to settle down, that would be yet another driving force for revitalizing the city. If that happens, this project would have far greater significance.

Generally speaking, cultural and language barriers make foreigners feel frustrated because they are unable to communicate their thoughts in full, particularly in initial stages of living overseas. Local people’s efforts to better understand how foreign residents feel would be the key to their long-term settlement. “It seems that Indonesian people are comparing notes with one another about how welcoming and friendly Kesennuma people are to foreign technical trainees,” Ms. Nakagawa said.

The Laboratory for Global Dialogue already has its 2024 spring project underway. “We are thinking of holding an art workshop in the local shopping street which has long sustained this fishing community. It is home to a wide range of age-old stores from a liquor shop to a Japanese tea retailer, a Kimono seller to an earthenware store supplying dishware to fishing vessels,” said Ms. Nakagawa. “Many of these businesses are not doing so well these days, but they have a long enough history. I think it will be interesting if we visit these stores with young Japanese people and foreign technical trainees, listen to what store owners have to say, and do something together.”

How disaster-affected communities thrive together

According to Mr. Watanabe, children in Aceh received a flood of support from overseas, including aid supplies from Japan, following the Sumatra earthquake. Those Indonesian children have grown up and this time, as college students and working adults, have offered support to exchanges between Indonesian children and Japanese elementary school children who survived the Great East Japan Earthquake. There is an growing cycle of mutual support among different generations between the two disaster-hit communities.

But still today, foreign technical trainees are often seen as a mere inflow of labor force from abroad. How to embrace them as members of the same local community, not just as workers, is an important question posed to the people of the host nation. In that sense, these two grant-awarded projects have led to learning experiences for both Japan and Indonesia, enabled local communities to connect directly across the border, and opened the possibility of members of diverse backgrounds living together in the same community.